Intro

Digital health is a key enabler of efficient, high-performing health systems. So what a national health platform does is set the rules of the game.

Can digital health enhance national health systems and what role can digital ecosystems play?

WHO is extremely excited about digital health as a catalyst to strengthen health systems. Many health systems struggle with limited resources to achieve large ambitions. And without tools like digital health to optimize how those limited resources are allocated, how services are delivered on time to those who need it the most, the resources are misspent. And so digital health is a key enabler of efficient, high-performing health systems.

How should national health systems shape digital transformation?

So it’s absolutely critical that digital transformation not happen in a chaotic manner. Over the last two decades, we’ve seen billions of dollars be spent in a discordant way, not achieving the levels of impact and scale that we’ve hoped for. So national health systems and governments need to have a clear vision of where they want the countries to go, as well as an architected plan or roadmap for how that transformation occurs. Once that architectural blueprint is in place, then there is scope for many actors to help advance the goals of that blueprint.

How important are quality, truth and trust in designing digital health care landscapes?

Those are three very important words, quality, truth and trust. Quality means making sure that the content and the standards on which these systems are built are the gold standards, and that’s the role of organizations like the World Health Organization. Truth and trust are things that have been eroded significantly over the past decade with the advent of misinformation and disinformation, fake news, et cetera. And so it’s absolutely critical that we leverage tools like digital health to make sure people have access to truthful, reliable information on which to base the health care decisions they are making.

How can national health systems prevent data monopolies and loss of control?

The national health systems and governments have a strong responsibility to ensure that the sovereignty and privacy of individual data is always protected. The importance of data ownership by individuals and the decisions as to how that data is used must always reside with the individual from whom that data comes. However, in large systems, it’s important that government sets the rules of engagement and the parameters or boundaries within which tech sector and other industry and private sector partners can play so that they support the mission of the public health system.

What role could a national health platform play in the personalized and human-centered health care of the future?

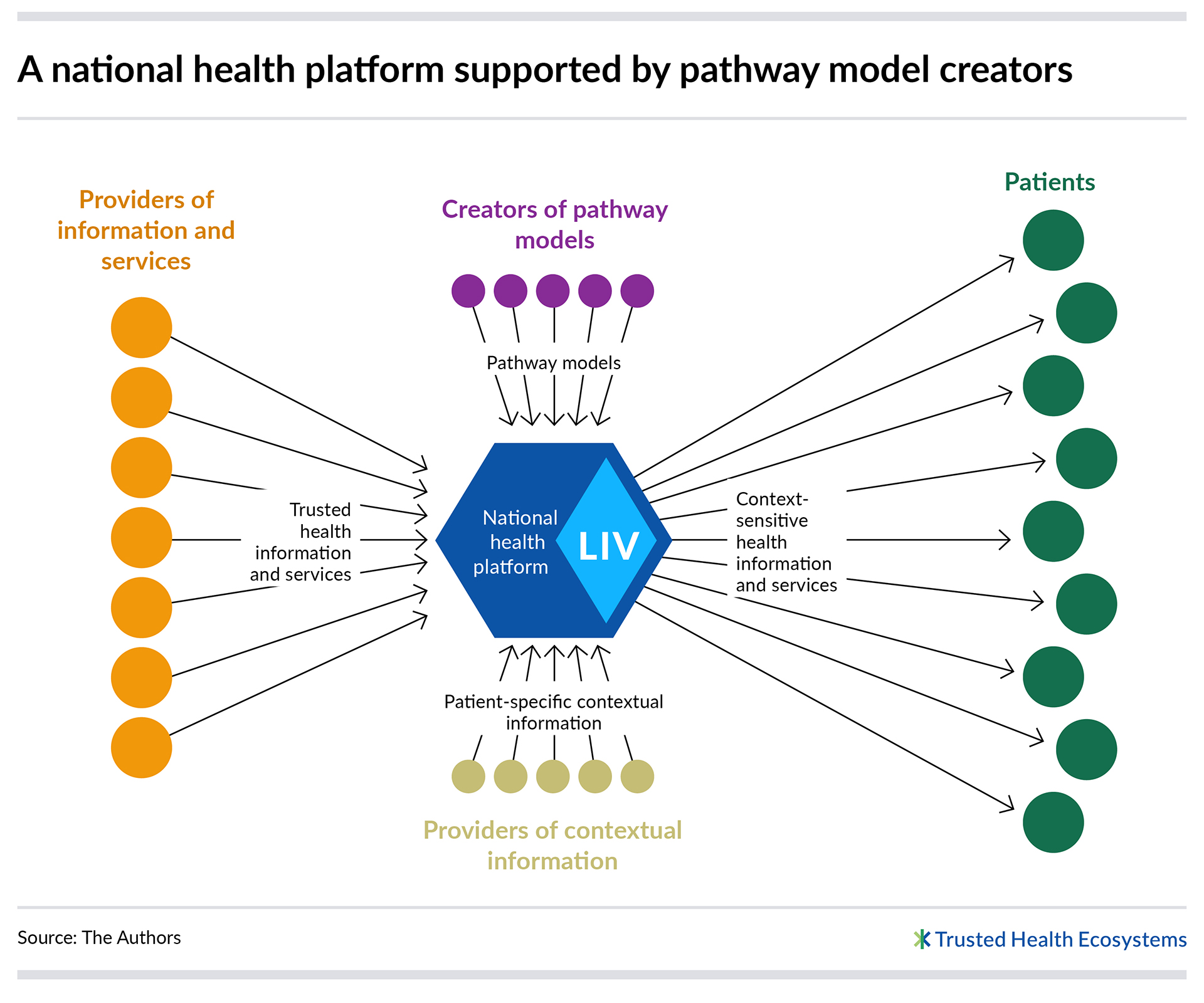

So what a national health platform does is set the rules of the game. It sets the boundaries and the guardrails within which all of the different actors can play together. By setting the vision, by setting the architecture, by selecting the standards, what we do is we enable all of these different solutions and innovations to thrive, not as separate innovations, but together as an interconnected system, ultimately keeping the patient or the individual at the center of all of the different pieces.

Expert

Dr. Alain Labrique is Director of the Department of Digital Health and Innovation at the World Health Organization. He is the founding director of the Global mHealth Initiative at Johns Hopkins University and editor-in-chief of the Oxford Open Digital Health Journal. An infectious disease epidemiologist and population scientist, he was a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health until September 2022. Labrique was the lead author of the 2012 Bellagio Declaration on mHealth Evidence and has authored more than 150 publications in top-tier journals, as well as numerous book chapters and technical reports on digital health.