The software architecture of a digital platform illustrates its structure, but also offers information regarding expected costs and the technical feasibility of certain requirements. In the case of the national health platform outlined here, the architecture will follow the basic pattern of other intermediary platforms, but can be elaborated in detail only once all requirements necessary for implementation have been defined and all open questions conclusively answered. During the concept development stage, some questions were deliberately left unanswered so as to provide flexibility and avoid building any premature decisions into the process. However, the conceptual decisions already made, along with the determination of roles and tasks of the platform in the digital ecosystem, make possible an initial overview of the required components and their interactions.

Based on the preliminary conceptual considerations (see Conceptual considerations: an overview), system boundaries can be identified that clarify what lies within the scope of the national health platform, as well as which directly neighboring systems are to be connected via interfaces. However, the considerations described here do not represent an implementation-ready software architecture that already encompasses all relevant architecture drivers and technological aspects. Their identification and refinement will be the subject of further conceptual work.

Participating ecosystem actors

The focus here is on the national health platform as a technical backbone brokering context-specific digital health information and services. The platform has the task of providing the essential functions needed to manage users and content. It also constitutes the technical link between the various ecosystem actors. Apart from the platform operator, these actors include:

- Providers of health information – for instance, information on diseases, prevention, health care structures and so on, in various formats.

- Providers of health-related services – for instance, online appointment scheduling, hospital search tools, pain diaries, etc.

- Providers of contextual information – personal information that provides clues regarding patients’ situational information needs.

- Developers of pathway models – indication-specific templates describing the expected trajectory of informational needs, along which specific health information is presented to individual patients as it becomes relevant.

- Patients

The platform and its interfaces

The core task of the national health platform is to relay health information and health-related services to the right people at the right time. This will usually be triggered by events, for instance a visit to the doctor or the expiration of a time period such as “six weeks after taking sick leave.” Such events will in turn be derived from incoming contextual information, which triggers the national health platform to deliver the appropriate information and services to patients along one or more currently relevant pathway models (see Conceptual considerations: an overview). This core functionality of brokering health information and services requires a number of interfaces, which are presented below:

- Interface for the inclusion of health information: This interface makes it possible to store health information on the platform so that it can be associated with patients’ situational informational needs based on certain characteristics and made available in a personalized feed (see Discover more, search less – prototype of a national health platform). In addition, this information can be retrieved via a semantic search.

- Interface for the inclusion of services: The inclusion of services is analogous to the inclusion of health information. Services are also made available to patients on a situational basis.

- Interface for the inclusion of individual contextual information: The transmission of individual contextual information about patients requires interfaces that allow for automated communication between systems. The exchange of data via these interfaces takes place exclusively on the basis of patients’ differentiated consent, as given to the provider of this contextual information; this could include the electronic health record (ePA) or various providers of fitness and health data. At the interfaces for the transfer of contextual information, the platform can check whether user consent has been given before allowing the transfer to take place. Different contextual information from different providers may require customized interfaces in each case, with the national health platform subsequently harmonizing the incoming data.

- Interface for managing pathway models: The templates are created via a graphical user interface and stored on the platform. The same interface can be used to manage, revise and improve pathway models. Likewise, it facilitates collaborative modeling involving multiple creators.

- Interface for patients: Patients access the functionalities of the national health platform via a graphical user interface – for example, in the form of a website or app for mobile devices – most typically to obtain health information or access health-related services. Additional access methods other than this traditional interface can be used, especially voice-based user interfaces. Patients are authenticated via the healthcare-sector digital identity planned for inclusion in the Telematics Infrastructure 2.0, which ensures that all data can be associated reliably with specific patients, and accessed only by them.

Health information is made available by certified providers by means of a dialogue-based process. This helps the various providers submit their information to the platform in such a way that it can be linked to pathway models and displayed to patients or found by them via a search. The actual content – such as an informational text or a video – is not transferred to the platform in this process, but remains with the provider. Instead, a link is created and enriched with metadata such as the date of creation or the sources used.

The health information is transmitted to the national health platform through the previously mentioned interface. This interface can be implemented in two forms. On the one hand, the platform itself can provide a graphical user interface. This website or application would be usable by health information providers, and would support them in submitting their information and entering all the necessary details.

On the other hand, this interface can also be designed to accept data from other systems without any active intervention by users. This requires supplementary interfaces on the part of the health information providers, specifically in the content management systems within which the information is originally prepared. These systems transmit authorized information to the platform. This has the advantage that providers do not have to engage with an additional system, and can remain in their familiar working environments.

Health-related services are handled similarly to health information. This means that certified providers will be given support in linking their services to the national health platform. As with the health information, the services are not transferred completely to the platform. Rather, a linking strategy is used: The platform receives a reference to a service, including descriptive metadata, in order to display this to patients along a pathway model.

Throughout the healthcare system, various actors accumulate contextual information that sheds light on patients’ situational information needs. Capturing this in a uniform format aligned with existing standards is critical to the success of the national health platform. I will discuss one such possible standard below. The basis for this uniformity is the interface specified by the platform, through which third-party systems transmit data. Currently, the most important data provider is Gematik, the state digital agency, which bundles all the data that doctors’ practices, pharmacies and clinics pass on via their various administrative systems in the form of the electronic health record.

The interface should allow the integration of other sources of contextual information in addition to the electronic health record. This could include health insurance companies or health data platforms such as Google Health or Fitbit, for example. Assuming that patient consent has been secured, the various actors would transmit this data to the national health platform. Since the exact formats of the data from the different providers are not yet known, it is likely that different types of interfaces will be offered for various groups of providers. As a result, the data may subsequently be harmonized on the national health platform.

The interface outlined here is utilized by a number of systems. It is not used by patients themselves, and does not provide a graphical user interface, since individual contextual information is automatically generated and transmitted by the information providers. In the absence of automation, it would not be feasible to keep such a large quantity of data sufficiently up to date. Nevertheless, this interface must also contain authentication mechanisms, thus ensuring that only authorized systems can transmit their data to the national health platform.

Creating models for patient information pathways requires expertise regarding the trajectory of patient informational needs and knowledge of the typical stages of a disease. For this reason, the templates are created exclusively by certified actors (see Conceptual considerations: an overview). At the same time, pathway models are expected to be complex, making it useful to have a visualization. The graphical user interface for interacting with pathway models will be accessible on the national health platform to appropriately certified stakeholders or their institutions.

Finally, we consider the perspective of the patients, who are presented with relevant health information and services based on their individual contextual information. They use the platform’s user interface to access the digital ecosystem in order to obtain information and services relevant to them along pathway models or – based on their individual needs – to search for information and services of verified quality. In addition, to ensure respect for data privacy, patients are given the ability to control how their data is used. This can be done via a privacy dashboard, such as the one being developed and tested in the D’accord research project (https://daccord-projekt.de).

Patients are authenticated via the digital identity provided for in the Telematics Infrastructure 2.0. This authentication facilitates the link to personal data from the electronic health record, which could serve as a primary source of contextual information, especially at the outset. In addition to this avenue of access, other mechanisms can be created to engage patients in the digital ecosystem. For example, authorized service providers might send SMS text messages that allow for direct links to the national health platform’s user interface.

Further conceptual steps

The final selection of suitable frameworks and technologies should be based on a requirements analysis and a detailed architectural design that expands upon and refines the broadly sketched requirements identified thus far. Non-functional requirements must be given special consideration in this regard. The topic of IT security was addressed in the previous section. Performance and scalability are also extremely important, as high user numbers can be expected, given that the platform is to be available to all patients in Germany. The large number of users means in turn that there will be a very large inflow of data to be processed by the platform. Given such loads, the technologies selected for implementation and the underlying infrastructure must allow for scaling.

Another essential non-functional requirement to be considered is the user experience (UX). Since the national health platform is open to all patients, and should be easy to use for everyone, consideration must be given to the special needs and preferences of different user groups, some of which are particularly vulnerable. These include elderly people or patients with a cognitive impairment, for example. Special attention should be paid to these groups during the design process.

The requirements analysis also determines the platform’s additional functionalities, including user and authorization management, pathway model management, and the instantiation of pathway models for patients. This refers to the assignment of specific health information and services to certain individuals, and their display via the platform, based on those individuals’ contextual information.

Framework for deployment and hosting

The core of the national health platform is the software itself, which must be made functional via distribution to one or more servers. This process is called “deployment.” In addition, it is required to operate the runtime environment for the software, which is referred to as “hosting.” Moreover, the platform will process or convey large quantities of data, ranging from user data and identifiers to links to health information and services to contextual information. Some of this must be present on the platform itself in order to be processed appropriately. All this data must also be stored, or hosted, on one or more servers.

The hosting of the platform and all stored data must of course be carried out in a technologically state-of-the-art way. This means that data handling must comply with the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and in the case of health-related data, with the requirements of the special protective measures defined by the GDPR. As the platform’s IT architecture is further refined, a number of decisions must be made regarding deployment. For example, a number of issues must be resolved, including which parts of the overall system are to be deployed where, and how this is to be done; and which organizational units are to be responsible for hosting them in each case. For example, the software hosting can be separated from the data hosting, with security measures put into place on both sides. Monitoring data flows on both the software and database sides and physically separating the servers will make it more difficult to compromise the system as a whole. Measures of this kind would help achieve a higher level of security and data-handing reliability

Specific analyses of potential attack scenarios are additionally needed in order to protect the national health platform. These must be carried out as the software architecture is designed. In principle, one goal should be for the hosting, including the storage of backups, to take place in Europe. Moreover, this should be handled by an entity recognized within the healthcare sector as being trustworthy.

Event-driven architecture

Health information and services are largely provided using the push principle – that is, patients receive the information relevant to them along the pathway models without having to take action themselves. Regardless, patients can also use a traditional search function. When matching search hits to queries, the platform can use all available contextual information to display matching results. This information can be used to create an individually tailored ranking of search results analogous to that provided by established search engines. In contrast to these, however, the national health platform can as needed report transparently on what specific contextual information, with which weighting, has led to a particular ranking of search results. This helps to gain the trust of both patients and the providers of health information and services.

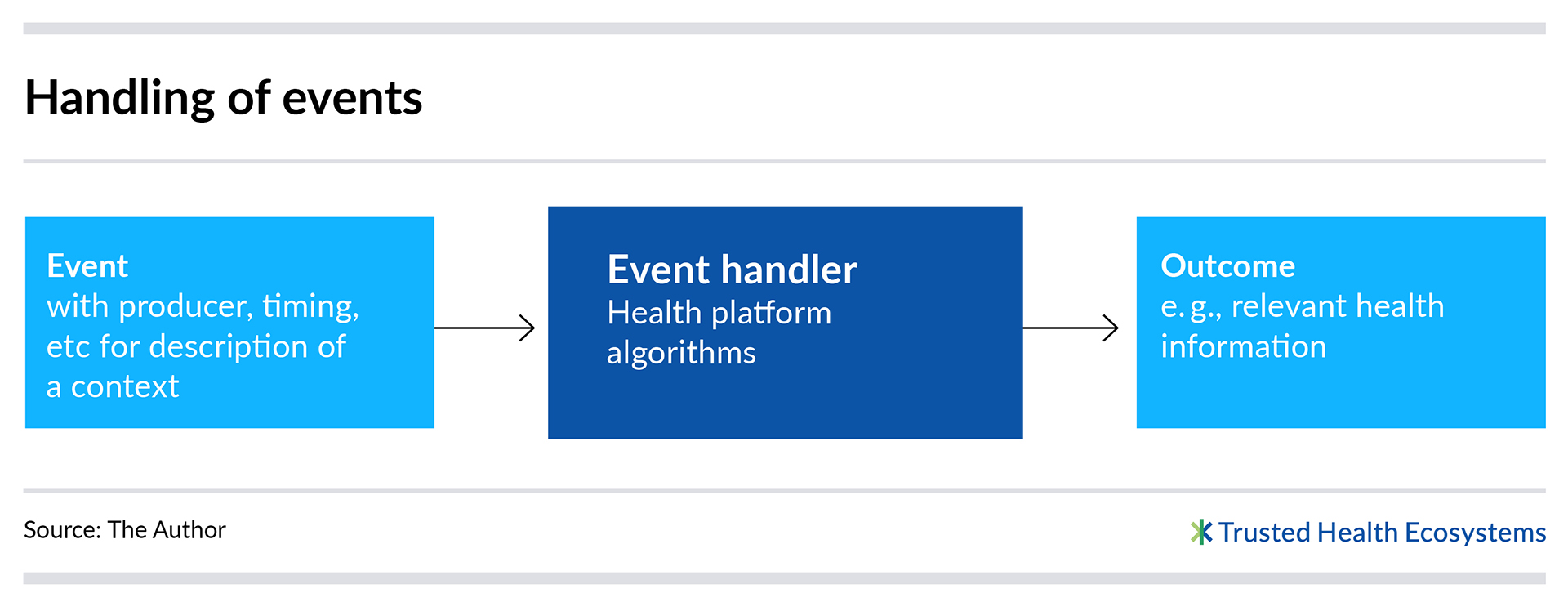

A system like the national health platform outlined here can be technically represented using what is called an “event-driven architecture.” An architecture of this kind focuses on the communication between different components in the overall system that takes place as events occur. Each event is triggered by an event producer, and is then processed by an “event handler.” This technical subsystem determines the subsequent actions based on the producer, timing, type and content of the event – for example, it may determine the appropriate health information to display to a patient.

Event-driven architectures are an established concept in software engineering, with a number of technical frameworks already in existence that can facilitate implementation. The Apache Kafka message broker (https://kafka.apache.org) offers one such example of a possible implementation strategy. Apache Kafka is a versatile technology that does not incorporate domain-specific features. In contrast, frameworks also exist that incorporate or define specific standards and functionalities for handling health-related data. Stanford University provides an open source framework for building healthcare-sector ecosystems called Spezi (https://github.com/StanfordSpezi). This framework defines an architecture that facilitates the exchange of health-related data with other systems by implementing the HL7®-defined FHIR® standard for the exchange of health-related data (https://www.hl7.org/fhir/). It would be conceivable – after an in-depth analysis of the requirements and the framework – to build selected parts of the platform on Spezi.

Feasible and open to new ideas

The considerations presented here regarding the technical implementation of a national health platform outline the basic functionality and establish the technical feasibility of the concept. At the same time, we show that the “brokering” model – that is, the provision of health information and services based on patients’ individual contextual information – is feasible. This is especially true if the platform can build on standards and open-source frameworks such as Stanford’s Spezi, as this can reduce effort and costs while decreasing dependence on proprietary solutions.

In addition, according to the concept, the national health platform is limited at its core to serving as an intermediary for the brokering of relevant information and digital services. This means the platform itself does not engage in the editorial creation of health information, the development of services or the acquisition of individuals’ contextual information. This constellation, which is typical of digital ecosystems, makes it possible to distribute responsibilities, and thus focus resources on quality assurance and the automated presentation of relevant information and offerings to patients.

The remarks in this paper deliberately do not specify a specific system architecture, and do not offer any preliminary technical definitions. The final determination of the appropriate architecture and technologies to realize the platform and its interfaces will be made after the functional and non-functional requirements have been worked out in detail and documented.

Author

Dr. Matthias Koch is a software engineer at Fraunhofer IESE, where he heads the Digital Innovation Design department. He has been designing innovative software solutions since 2012, with clients from the business community and in research projects. He has focused in particular on the areas of requirements and user experience engineering, as well as on the implementation of innovation workshops. Koch’s work involves the design of methods and tools for building digital platforms, especially in the area of digital ecosystems.