Our vision of a national health platform is all about trust. This includes ensuring that users can rely absolutely on the quality of the content and services being offered. But how can this goal be realized in an era of disinformation and conspiracy theories? In a subproject called InfoCure, we explore the issue of how good information quality can be made visible, and how disinformation can be contained.

More and more people today use the internet to inform themselves about health-related issues, often using major social media platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, Facebook and Telegram. Through these networks, disinformation and false information can spread faster than ever before. At the same time, the platform operators’ algorithms generate lists of continuously refreshed content that build on previous search patterns and confirm users in their previously held assumptions and attitudes. These “reinforcement loops” are themselves enhanced by the digital network’s social environments, which often reflect users’ own opinions back to them, and thus create fertile soil for disinformation and conspiracy theories.

“The rapid spread of health misinformation through digital platforms has become a serious threat to public health globally.“

Andy Pattison, WHO (2021)

Information quality as brand essence

Trust is formed in digital worlds through the responsible handling of personal data or appropriate measures to increase data security, for example. Yet ensuring that the information and services offered are reliable and of high quality is another basic prerequisite for the development of trust in digital infrastructures. To date, social networks have provided virtually no means of indicating the trustworthiness or credibility of an information source, making it very difficult to ascertain the methodological quality of the information delivered. The same is true of digital services. A national health platform must make a clear difference here.

Quality-assurance strategies for health information today have focused primarily on the review of individual informational elements such as texts or videos. However, this approach demands considerable human and financial resources, and costs one thing above all: time. Yet digital ecosystems and their platform approaches are so successful precisely because they provide their services largely digitally, and can thus grow very quickly within a very short period of time.

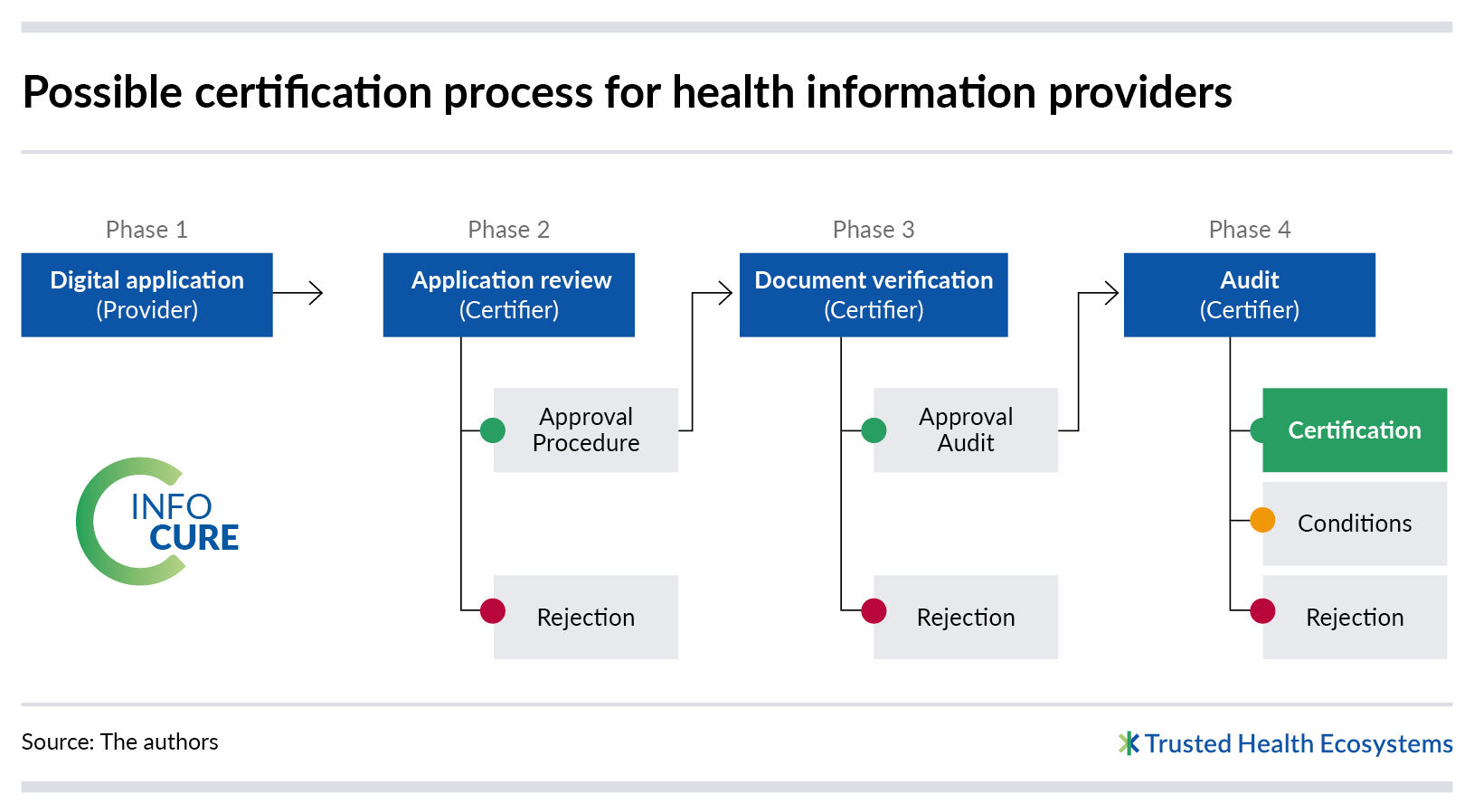

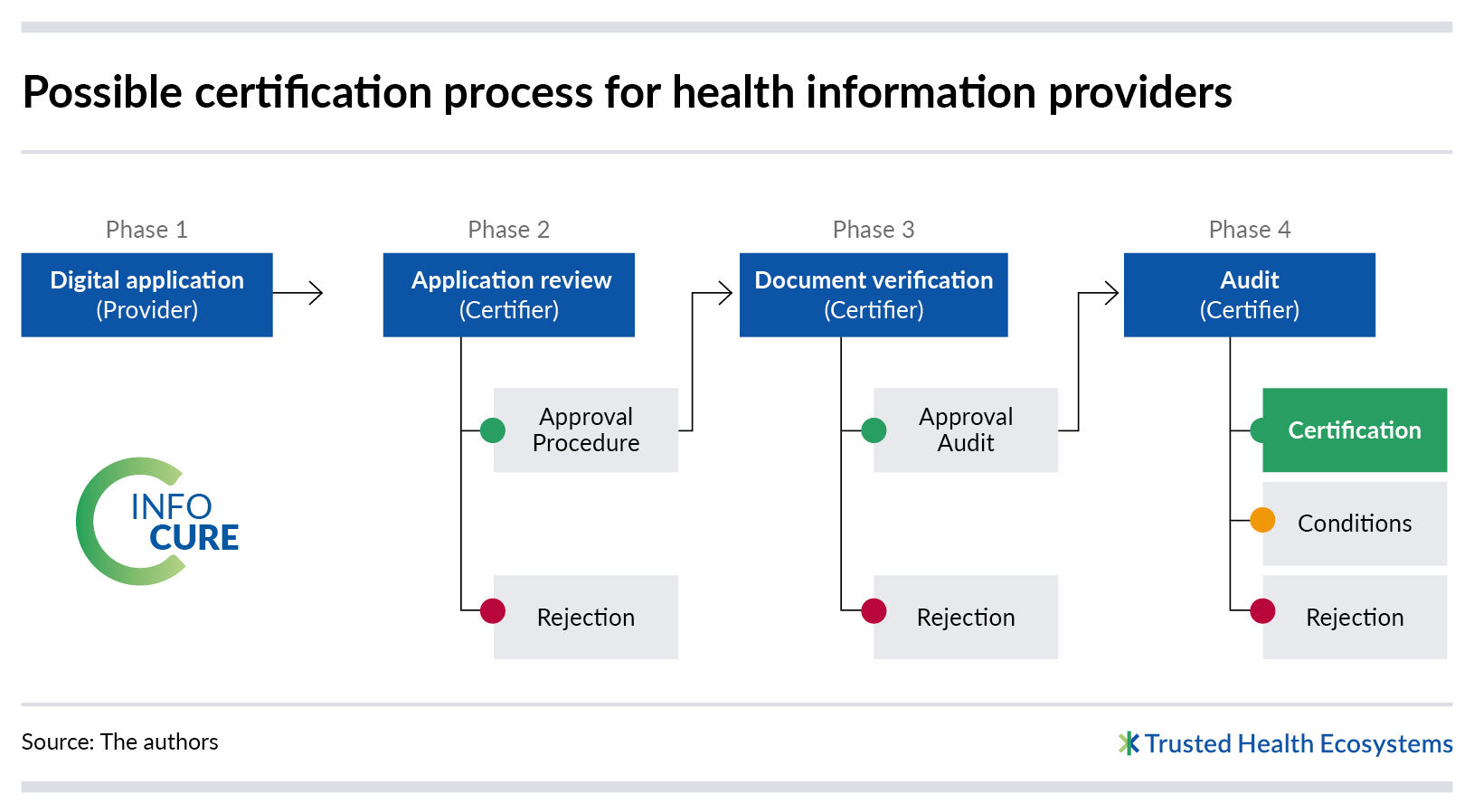

Provider certification

To keep up with this rapid pace, platform operators need a quality assurance approach that evaluates the providers of information rather than focusing on individual information. Structural aspects (e.g., expertise) and criteria relating to process quality (e.g., use of certain methods) could be used in these assessments. However, a voluntary commitment to quality assurance is unlikely to be enough to give platform users a sufficient level of confidence. Instead, an external audit by an independent body in the sense of a certification procedure would be required. A multistage audit-based procedure is a good way of obtaining a reliable assessment of a provider’s structures and processes.

This kind of quality-oriented selection of trustworthy information providers could reduce the risk of disinformation and misinformation to a minimum. In combination with other instruments such as user feedback and digital review procedures, the platform’s information and service quality as a whole could come to be regarded as a trusted space, supporting users and providing them with significant relief in their search for credible information.

Diverse applications possible

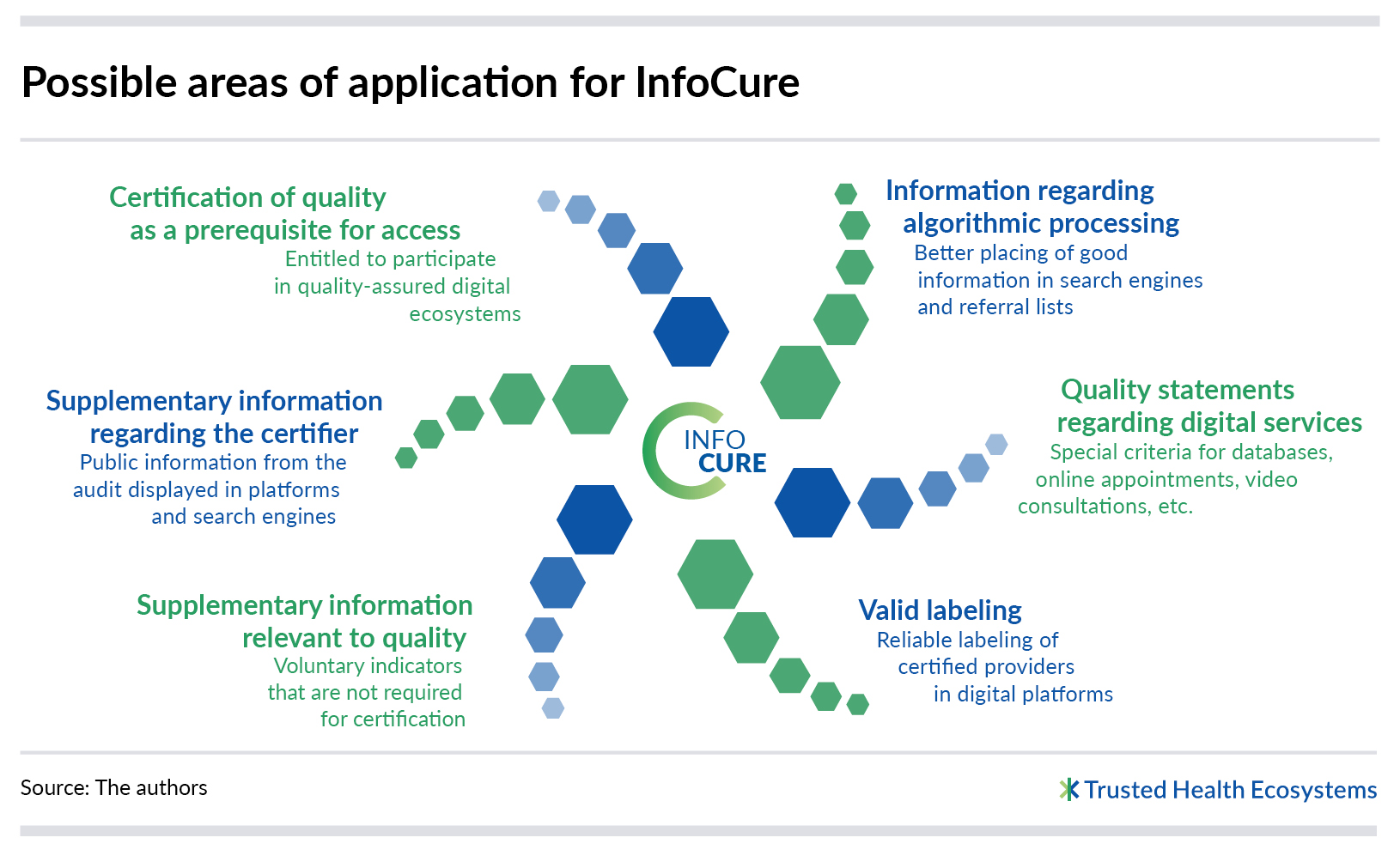

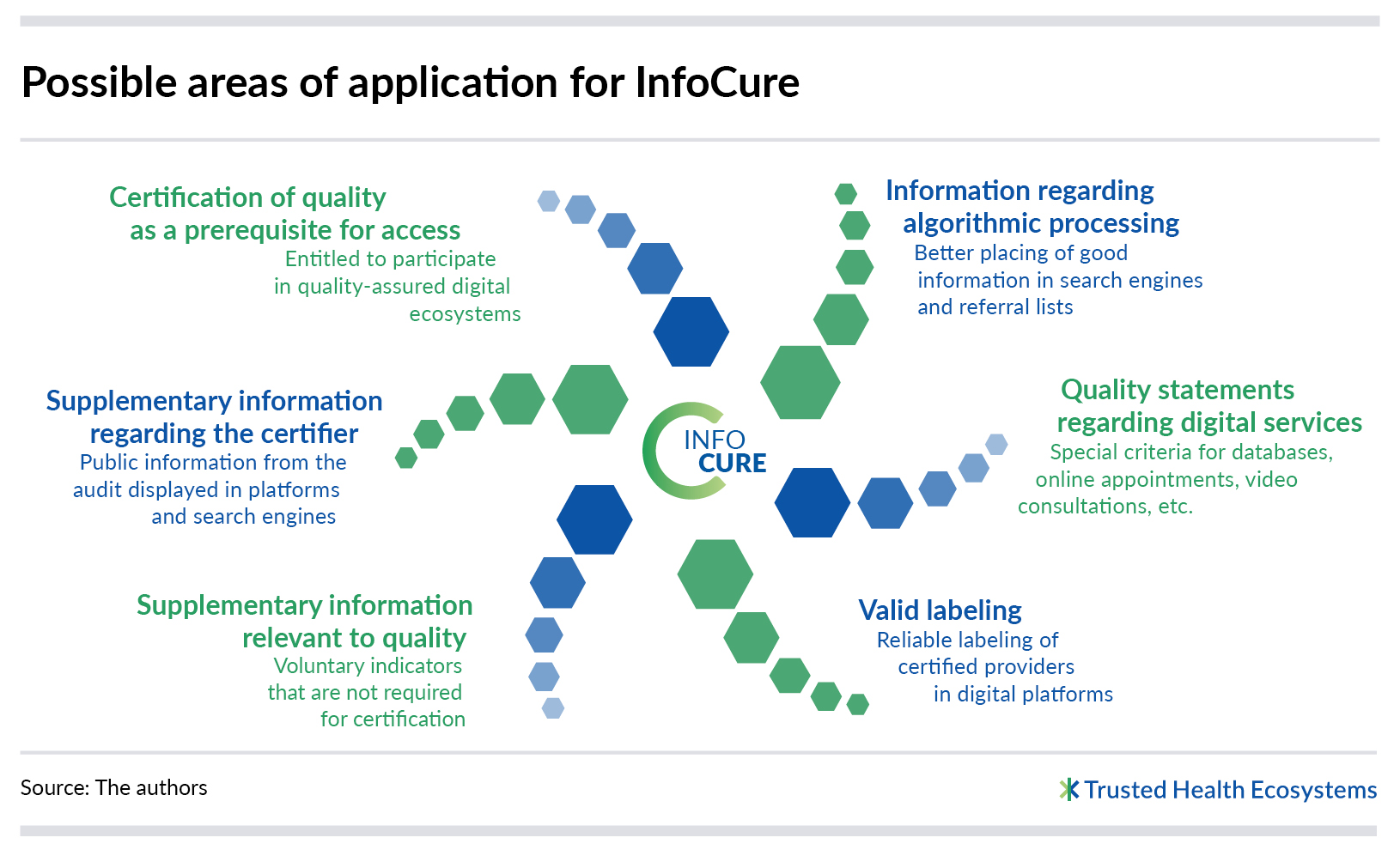

By becoming certified, health information and service providers could qualify for participation in the national health platform’s digital ecosystem. However, this certification does not have to be limited to this access-granting: Indeed, once a provider is certified, the digital certificate could be used for many other purposes.

Operators of major search engines could use this information as a means of identifying reputable providers for the first time, and incorporate this new knowledge when calculating the relevance of search results. Platforms and search engines could label trustworthy information providers accordingly, and background information on the providers would be visible to users. This would reward all those providers who go to great effort to ensure the quality of their information .

Of course, a single set of rules cannot cover all types of information. For example, patient descriptions of personal experiences can convey valuable information that relates to the psychosocial aspects of dealing with a disease. Different criteria must therefore be taken into account when evaluating the quality of such offerings. A similar logic applies to socio-legal information, which must meet completely different quality requirements than medical content.

Finally, it should be noted that in addition to pure information offerings, the health-related internet is full of digital services such as online appointment functions, databases, video-based online doctor visits and second-opinion services, all of which must be considered on their own terms. In the medium to long term, the original certification for medical patient information can and should be expanded in a modular way to include additional areas of application.

International approach

Assuring the quality of health-related information in the digital age is a challenge that cannot be addressed solely at the national level. For this reason, international standards must be taken into consideration, and must be strictly adhered to in the interests of interoperability. Furthermore, in order to achieve impact beyond national borders, the development of new quality standards should take place in the context of an international expert dialogue.

In our search for relevant standards and projects, we became aware of an initiative led by the U.S. National Academy of Medicine (NAM). In 2021, with input from an independent advisory group of scientists, this project developed and published a set of basic principles and attributes that could be used to identify credible sources of health information. The goal of the initiative was primarily to provide social networks and platforms with criteria for identifying providers of trustworthy health information.

The principles state that, to be considered credible, sources should be science-based objective, transparent and accountable, hence they provide a good foundation for the evaluation of information providers. However, to use these as the basis for a certification procedure, further operationalization is required. In the course of dialogue with international specialized partners and the World Health Organization (WHO), the idea has emerged of translating these principles into a concrete indicator system that could serve as the basis for an audit-based certification process for health information providers. The idea will be realized via a clear and familiar division of tasks: The frameworks and standards will be defined consensually at the international level, while the actual certification will be performed by national-level institutions or organizations.

Working group has begun its activity

Numerous past initiatives have focused on the assessment, description and development of information quality in the health sector. These provide a very good starting point in developing a set of such indicators. The current project differs from these existing initiatives in its clear focus on providers and international standardization, and in the fact that major tech companies are today facing mounting pressure to deal with disinformation. The approach described above offers a valuable opportunity to make high-quality information more accessible to patients and support healthy decisions through good information, and thus to make a major contribution to the promotion of health literacy.

„Digital platforms have a uniquely powerful opportunity to enable worldwide access to high-quality health information.“

Victor J. Dzau, NAM (2021)

In 2023, the Bertelsmann Stiftung, together with the German Network for Evidence-Based Medicine and Health Literacy Germany, established an international working group that will define the tasks ahead in the context of a scientific discussion paper, and additionally draw up initial proposals for the development of an indicator system. In the medium term, the creation of InfoCure is intended to provide an international certification system for credible providers of health information and services that will initially be implemented in Germany, and then scaled up internationally in a subsequent step.

Bibliography

Burstin H, Curry S, Ranney M L, Arora V, Boxer Wachler B, Chou W-Y S, Correa R, Cryer D, Dizon D, Flores E, Harmon G, Jain A, Johnson K, Laine C, Leininger L, McMahon G, Michaelis L, Minhas R, Mularski R, Oldham J, Padman R, Pinnock C, Rivera J, Southwell B, Villarruel A, Wallace K (2023). Identifying Credible Sources of Health Information in Social Media: Phase 2—Considerations for Non-accredited Nonprofit Organizations, For-profit Entities, and Individual Sources. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202305b

Kington R, Arnesen S, Chou W-Y S, Curry S, Lazer D, Villarruel A (2021). Identifying Credible Sources of Health Information in Social Media: Principles and Attributes. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202107a

Schaeffer D, Berens E-M, Gille S, Griese L, Klinger J, de Sombre S, Vogt D, Hurrelmann K (2021). Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland – vor und während der Corona Pandemie: Ergebnisse des HLS-GER 2. Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Gesundheitskompetenzforschung (IZGK), Universität Bielefeld. Bielefeld. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4119/unibi/2950305

WHO (2021). WHO online consultation meeting to discuss global principles for identifying credible sources of health information on social media. Meeting Summary. Abrufbar unter: Summary-Global principles for identifying credible sources of health information on social media (who.int) (Zugriff am 25.07.2023).

WHO (2022). WHO and NAM encourage digital platforms to apply global principles for identifying credible sources of health information. WHO Departmental News, 24. Februar 2022. Abrufbar unter: WHO and NAM encourage digital platforms to apply global principles for identifying credible sources of health information (Zugriff am 25.07.2023).