Patients seeking medical assistance are usually required to answer several questions about their medical history. Physicians ask these questions to narrow the scope of possible diagnoses. This process, referred to as anamnesis, is an integral part of any medical diagnosis, and the contextual information it contains helps treating physicians or clinicians determine an appropriate treatment as a next step. Contextual information thus creates benefits for various areas of our lives. This idea also forms the guiding principle of the concept for a national health platform presented here.

In the field of medicine as well as everyday life, understanding contextual matters is incredibly useful when it comes to solving specific problems or providing advice to others. When someone asks us for directions to a particular destination, we need to at least know their current location and the modes of transportation available to them. If someone asks us for relationship advice, it’s important for us to understand the current dynamics of their relationship and situation.

A look at the world of IT that surrounds us makes this point even more clear. When we interact with software systems that lack context, they often seem limited. For instance, basic versions of search engines, which lack context, provide vast amounts of results. Searching for “restaurant” thus leads, among other things, to explanatory texts that define the term “restaurant.” While this might be the correct result for certain search intentions, most people query “restaurant” when they want to know which restaurants are nearby.

When the search engine automatically takes the user’s context into account, the results are suddenly much more meaningful: The user’s current location leads to suggested restaurants in the vicinity. If the software considers additional factors like the time of day or personal food preferences, the results become even more helpful, narrowing down the options to suitable restaurants that are currently open and align with individual preferences. Alternatively, there’s always the option to manually input contextual information, such as the location or the time of the visit. While such user inputs would also yield good results, they would also increase the effort required.

Search engines are just one example; there are numerous other software applications that, by incorporating contextual information, provide improved results. Examples include navigation systems that continuously require a user’s current location for reliable guidance, fitness trackers that base recommendations on a full set of observed body metrics, or matchmaking platforms that can only offer promising suggestions when traits and preferences are shared.

The wide range of software applications operating with the aid of contextual information, and thus delivering value, has ensured that the overwhelming majority of users are fundamentally familiar with them. These users willingly share their contextual factors with the software systems in order to access individually tailored offerings.

Features that are perceived as intelligent and particularly helpful almost always depend on the utilization of contextual information and fuel the ongoing growth of user expectations. Those aiming to create new successful services thus focus on increasing automation and enhancing user experience by bringing together existing information and contextual data.

Context is the key to real patient benefits

A central objective of the national health platform is to provide patients with trustworthy health information and services that are selected and tailored to suit their current health situation.

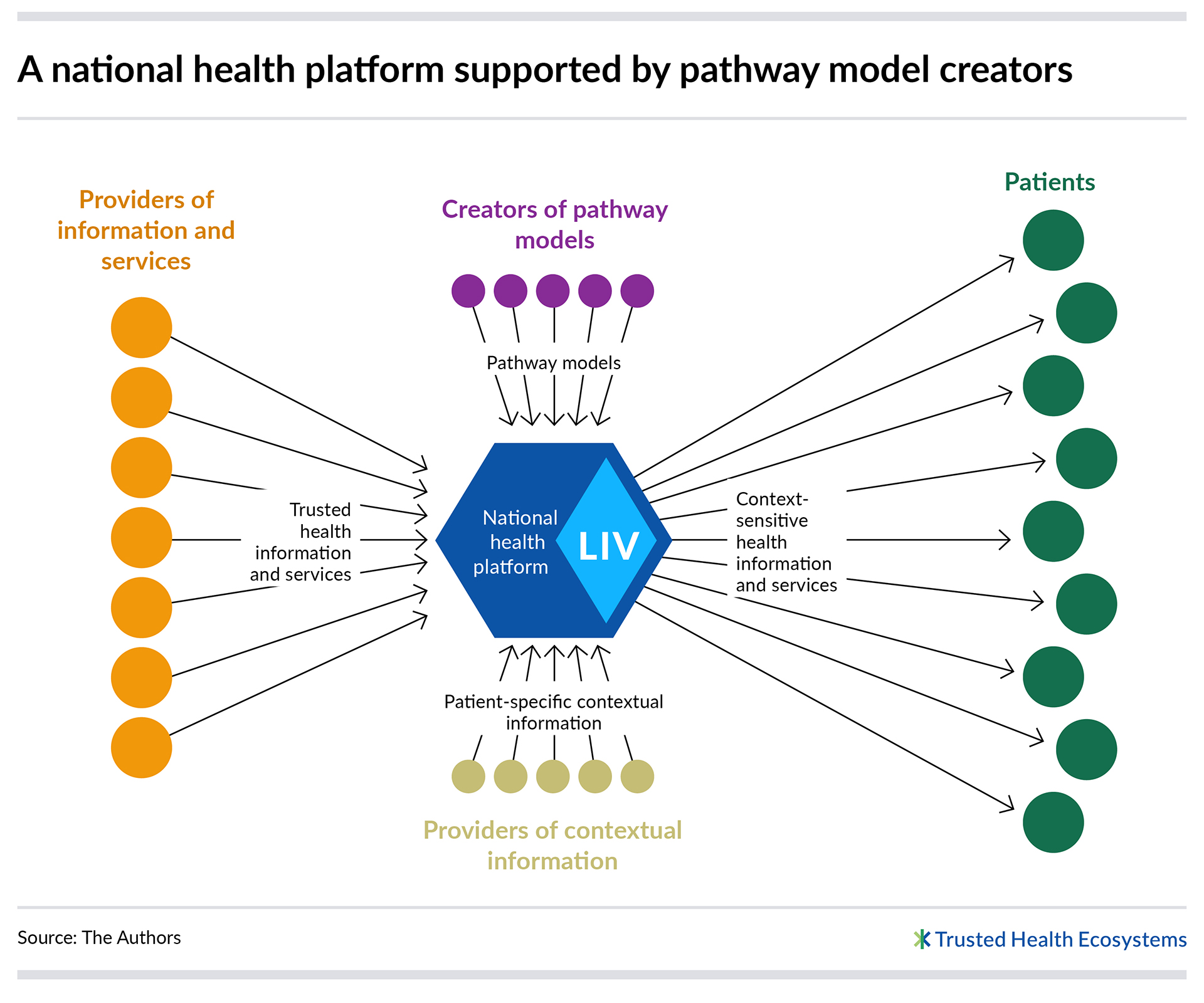

The figure below depicts a streamlined image of the national health platform. The platform envisions a process by which information and service offerings are delivered to patients without explicitly incorporating external contextual information.

The national health platform aims to generate the highest possible benefit for patients by offering reliable health information and services that are as relevant as possible to their current health situation. Achieving this goal would require each patient to manually input the necessary contextual information. This solution is simply not feasible in today’s world, as it would create significant user burdens and thus fail to gain any noteworthy traction. Nonetheless, patient contexts are essential to determining which information and services are appropriate for a specific individual.

The national health platform aims to generate the highest possible benefit for patients by offering reliable health information and services that are as relevant as possible to their current health situation. Achieving this goal would require each patient to manually input the necessary contextual information. This solution is simply not feasible in today’s world, as it would create significant user burdens and thus fail to gain any noteworthy traction. Nonetheless, patient contexts are essential to determining which information and services are appropriate for a specific individual.

The core concept of the platform proposed here is to harness contextual information that is already available in other IT systems (e.g., office management systems, electronic health records, or health trackers) for the selection of information and digital services on the national health platform. This would allow patients to determine which contextual information about themselves that originates with other IT sources can be integrated into their pathway and thus foster an improved user experience. The resulting quality in outcomes could constitute a strong unique selling point for the platform.

The core concept of the platform proposed here is to harness contextual information that is already available in other IT systems (e.g., office management systems, electronic health records, or health trackers) for the selection of information and digital services on the national health platform. This would allow patients to determine which contextual information about themselves that originates with other IT sources can be integrated into their pathway and thus foster an improved user experience. The resulting quality in outcomes could constitute a strong unique selling point for the platform.

How contextual information leads to specific patient benefits

Services and information that are provided automatically must be highly relevant to an individual’s situation if users are to embrace them. This is why the national health platform aims to embed information within a structured process of learning and interaction that results in a wide range of personalized patient information pathways (see Discover more, search less – prototype of a national health platform).

A patient information pathway refers to a tailored-to-the patient course of interaction in which the services and information offered are aligned with a patient’s unique situation. The customized assistance they receive is thus perceived as beneficial. Given the vast range of potential information pathways, it is not immediately clear, exactly, how this type of support can be generated automatically. Even for experts, making appropriate selections from an immense pool of information and service offerings can be challenging.

The solution lies in a newly created modeling language that enables experts to create pathway models as templates for the information needs that arise during the course of an illness. These pathway models take into account various aspects such as the course of treatment within a specific healthcare system, as well as different phases of disease management and (legal) issues related to benefits.

Pathway Model Creators

Developing such pathway models requires the presence of yet another role within the digital ecosystem: that of the pathway model creators. These creators are experts who draw on the typical trajectories of a condition, its treatment and its management to describe the anticipated information needs for a specific symptom. Employing a community approach here can help create an exhaustive and rapidly expanding knowledge base for the national health platform.

Processing contextual information is essential to the modeling process, as the envisioned trajectory is linked to information needs that can be expected over time. The situations in which patients find themselves, such as having to decide whether to have an operation or not, will determine which health information and services are presented to them. The expertise and experience of a broad range of actors from various scientific disciplines are thus integrated into the information pathways.

This involvement of an expert community is a cornerstone of quality assurance and generates modeled knowledge that can be verified and explained. Based on information about a given situational context, the modeled templates are adjusted and expanded over time. The combination of human expertise with technology, rather than the implementation of purely AI-based solutions, should bolster confidence in a national health platform.

If implemented, the national health platform would generate and utilize millions of automatically personalized patient information pathways. These pathways, guided by the pathway models, incorporate concrete and patient-specific contextual information to select the health information and services offered at any given time. These pathway models, which are loaded with professional expertise and experiential knowledge, thus form the missing piece in the puzzle that makes it possible to provide customized information offerings to patients.

If implemented, the national health platform would generate and utilize millions of automatically personalized patient information pathways. These pathways, guided by the pathway models, incorporate concrete and patient-specific contextual information to select the health information and services offered at any given time. These pathway models, which are loaded with professional expertise and experiential knowledge, thus form the missing piece in the puzzle that makes it possible to provide customized information offerings to patients.

What is meant by “context,” exactly?

In this article, so far, we’ve used the term “contextual information” in an abstract manner. However, when it comes to using the term with reference to data and information, there is considerable potential for misunderstanding. On the one hand, the specific nature of the data and information under discussion is rarely specified and, on the other, too little is said about intended uses, emerging benefits and the resulting protection needs. We therefore elaborate here upon the term “context,” offering clarification.

The concept of “context” is used in this article to refer to any information specific to a person’s situation that is available in IT systems and can be used to customize offerings to their needs. Contextual information can include, for example:

- Basic personal variables: e.g., age, gender, weight

- Patient preferences: e.g., preferences regarding information providers, preferences regarding information attributes (language, comprehensibility, etc.)

- Health status information: e.g., symptoms, medication use, utilization of healthcare services.

- Current information: e.g., on “events” such as a prescription for a new medication, being admitted to a hospital, situational moods and current well-being

- Information about interaction with the national health platform: e.g., articles already read, feedback on articles

Other types of pertinent information that are not classified as contextual information include reliable health-related information, such as explanatory articles about specific medical conditions. These resources, made available by providers, lack any association with an individual’s personal details.

Contextual information, in the context of the national health platform outlined here, always serves the direct purpose of enhancing benefits for patients. This objective also informs all efforts to protect this data.

Contextual information in trusted hands

In principle, there are a variety of actors in the market that could establish a digital ecosystem and, with the consent of patients, aggregate and process their specific contextual information within a platform. However, each platform operator will certainly bring their own values to the design of their platform. While conceptualizing the national health platform proposed here, we thus emphasized the need to establish a trustworthy institutional structure that handles sensitive contextual information responsibly. (see Successfully establishing health ecosystems – models from abroad)

Contextual information should always be processed for the sole purpose of delivering better user experiences and improved information and service offerings. This is the core focus of the platform; these pieces of information are therefore not retained indefinitely or used for other purposes. Unless data use has been explicitly authorized for other purposes, the data is only stored for as long as necessary to fulfill its intended purpose.

Patients should retain full control over how their personal contextual information is used through a dedicated consent system. They should be able, at any point in time, to select or determine which providers and sources of contextual information are used.

As a whole, the platform aims to create valuable patient benefits and clearly communicate them to all actors in the healthcare sector. The decisive issue here is that the responsible and transparent use of health data can generate welfare effects and individual benefits. Of course, safeguarding personal data is always a priority.

Context matters

Context is a critical factor in making software solutions useful and enjoyable. This holds true for all sectors and, of course, the healthcare sector as well. While people have long been enjoying these advantages in many other areas, they often encounter fragmented systems in healthcare that either fail to consider contextual factors or do so insufficiently.

Offering personalized information tailored specifically to a patient’s needs, patient information pathways enhance the user experience by saving the patient considerable time in finding the information and services that serve them best.

Authors

Dr. Matthias Naab and Dr. Marcus Trapp, co-founders of Full Flamingo, an eco-tech startup, aim to leverage the power of the platform economy for the greatest possible impact on sustainability. Before 2022, they held senior executive positions at Fraunhofer IESE, where they played a pivotal role in developing and overseeing the field of “Digital Ecosystems and the Platform Economy.”