Intro

How do we create ecosystems that improve the public’s health literacy and promote prevention?

How do we establish trust in a digital platform?

In my opinion, it’s important to state how you go about establishing and building trust. This involves two things: For one, there’s clarity. What purpose does the ecosystem serve for citizens? And on the other, it’s important to establish transparency.

Estonia stands as a notable example, in my opinion. They’ve legislated the specific purposes for which healthcare professionals can access health data, specifying when it’s permissible and when it’s not. They’ve also embraced transparency by allowing citizens to log in to their profile through the Estonian Central Health Information System and Patient Portal to track who has accessed their data.

What additional elements are necessary to make a healthcare platform appealing?

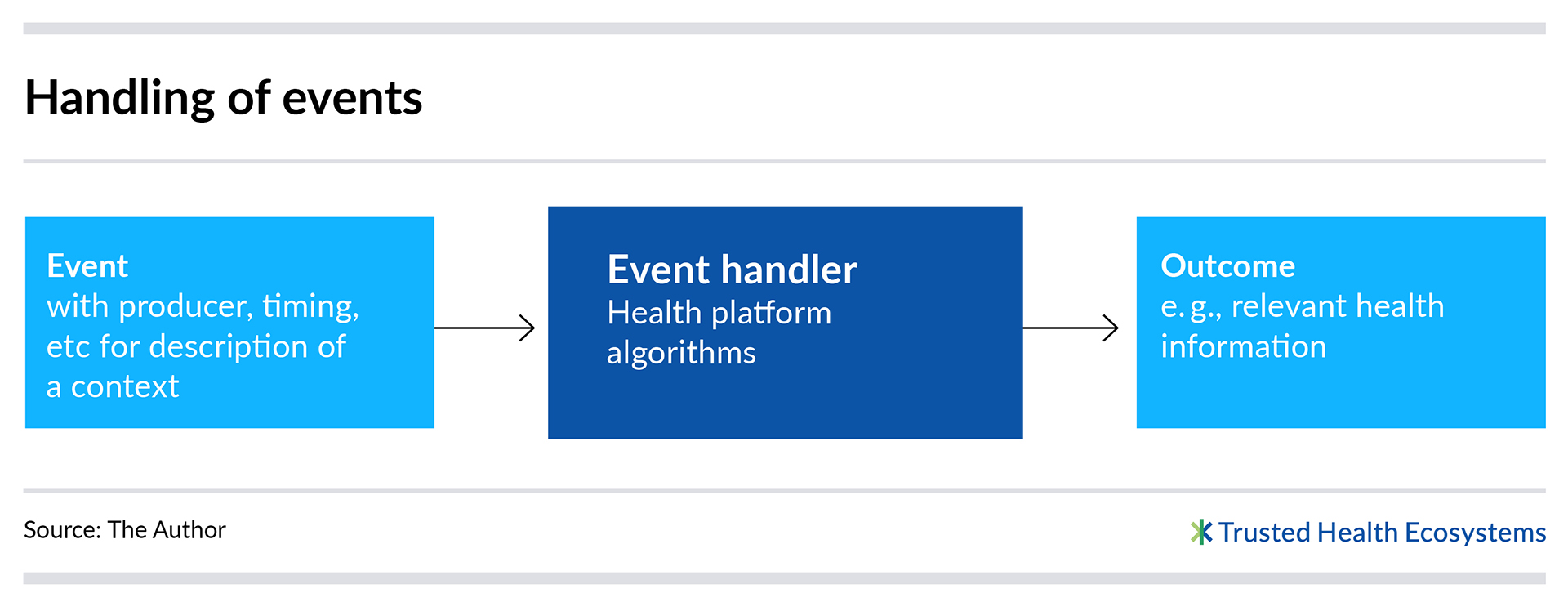

Utility is the key element. In the context of health platforms and health ecosystems, the focus is often on creating services that provide added value to both patients and citizens, as well as healthcare providers, such as nurses, caregivers, doctors and more.

These services are often linked with each other, with a single service benefiting both citizens and healthcare providers. It’s therefore crucial to develop these services with a user-centric approach and involve users and stakeholders from the outset. Ideally, this approach leads to the creation of a service that benefits multiple stakeholders and operates effectively and efficiently for those providing the service.

Denmark serves as a compelling example in this context. They actively engage user panels, conduct user interviews and surveys, and collaborate with citizens and healthcare providers to co-create services. This leads to the development of services that not only deliver value but also, due to effective and efficient management, enhance user engagement.

What objectives should a national healthcare platform strive for?

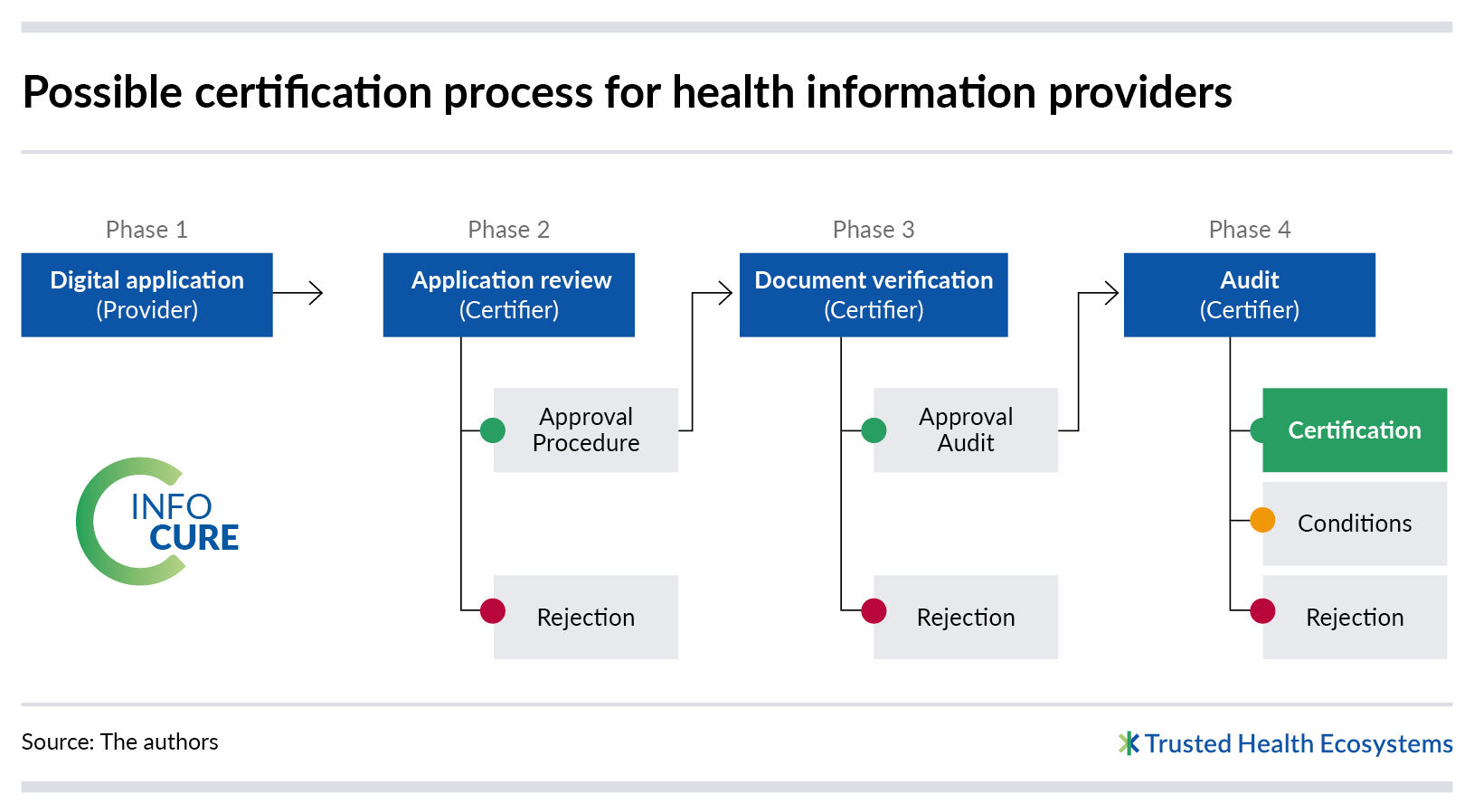

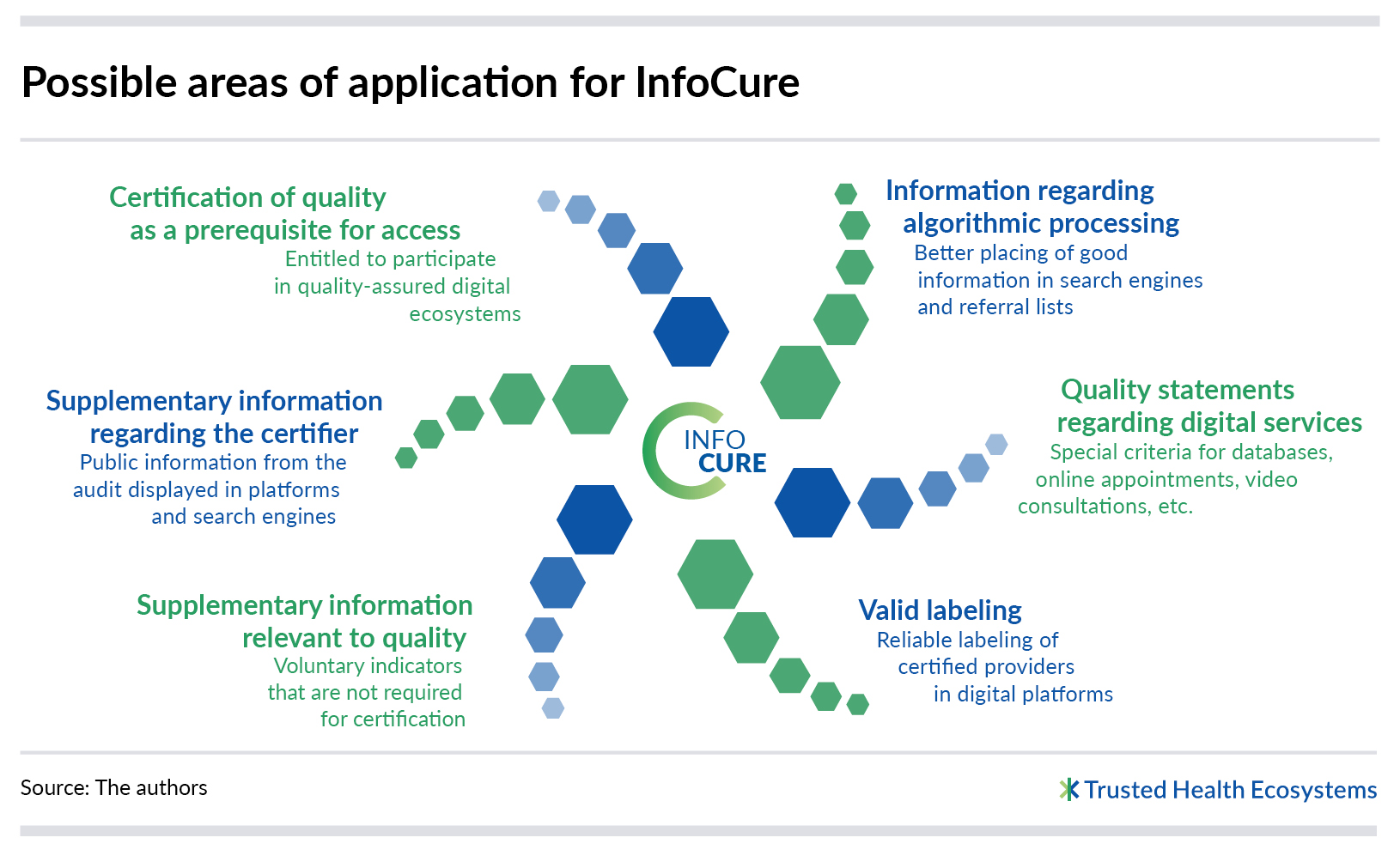

The ambition could revolve around establishing ecosystems that boost the health literacy of the population, simplify preventive measures, empower individuals to manage chronic illnesses effectively, and ideally, free up healthcare providers to spend more time with patients and less on administrative tasks. An important concept to consider is the creation of open ecosystems, where third-party providers can offer their services within the ecosystem, insofar as they meet specific quality, transparency and security criteria.

Israel has successfully implemented such an open ecosystem, with two noteworthy facets. First, health data exchange allows one doctor to access previous treatment information, which facilitates more informed decisions and improved patient care. Second, the involvement of third-party providers within the ecosystem, including startups and healthcare companies, fosters innovation on a national scale. This can prove to be a real boost to the country’s innovation advantage by bundling the innovative power of healthcare companies in creating a platform that makes innovative healthcare solutions more readily accessible to citizens.

Expert

Dr. Tobias Silberzahn holds a doctorate in biochemistry and is a Partner at the Berlin office of McKinsey & Company, Inc. His work focuses on healthcare innovation and the digital transformation of healthcare. Tobias also leads the global Health Tech Network, which brings together more than 1,800 health tech CEOs and founders, along with 250 investors and 300 corporations. He is co-publisher of the annual “eHealth Monitor,” a publication distributed by MWV publishing house that focuses on the digitalization of the German healthcare system. Within McKinsey, Tobias also co-manages a comprehensive health and well-being program that encompasses aspects such as sleep, nutrition, fitness, and stress management.