Achieving a sustainable digital transformation in healthcare requires more than technical innovation – it calls for interdisciplinary thinking and meaningful user engagement. As patients navigate an expanding landscape of digital services, treatment options, and sources of health information, they gain new opportunities to play a more active role in their care. To harness this potential and strengthen patient-centered approaches, a national health platform can serve as a trusted, centralized point of access. Its success, however, hinges on involving users early and often in the design process. The future of digital healthcare requires collaboration. The following article outlines key considerations for embedding user participation into the development of a national health platform.

A shared digital vision

National legislation – including the Digital Act (DigiG), the Health Data Use Act (GNDG), and the Federal Ministry of Health’s digital strategy – is helping facilitate the digital transformation of healthcare in Germany. Milestones such as the rollout of the electronic health record (ePA), the introduction of e-prescriptions, and new frameworks for leveraging health data under the GNDG mark critical progress. At the European level, the European Health Data Space (EHDS) is also generating momentum, aiming to strengthen health data use and facilitate cross-border care.

Patients – and all who engage with the health system – are at the center of these developments. This focus is essential. As digital tools and biotechnologies evolve, users are navigating an increasingly complex health ecosystem, characterized by a growing number of treatment and communication options, information sources and stakeholders. Global tech companies are also entering the health sector with user-friendly digital platforms, amplifying both the volume of choices and the burden of individual decision-making and responsibility (BMG 2023; BMG 2024).

The Trusted Health Ecosystems platform strategy complements national and international digitalization efforts. By curating and integrating trusted sources of information and services, it aims to strengthen health literacy and empower users to make informed decisions and participate more actively in their care (see Our concept – Bertelsmann THE). At the same time, it seeks to create a digital space built on trust – ensuring data protection, privacy, and user autonomy, while fostering data solidarity to improve population health outcomes.

A key to meaningful digital transformation in healthcare: Engaging users

User engagement is essential to ensuring that a national health platform responds to real-world needs. Thoughtfully involving users from the outset helps align digital solutions with the expectations and priorities of those they are designed to serve.

When platforms are developed with a user-centered approach, they are more likely to gain trust, improve satisfaction, and see broader uptake – all of which can support better health outcomes over time (Fischer 2020; Hochmuth et al. 2020).

Numerous initiatives and participatory approaches in research and development are helping to formalize and strengthen user involvement. Regardless of the specific context, one principle holds across the board: meaningful collaboration between developers, healthcare providers, and patients is vital to success.

Participatory approaches to developing a national health platform

Effectively involving users in the development of a national health platform requires drawing on a range of participatory research and design approaches. These methods can be combined in complementary ways to strengthen user engagement and ensure that the platform reflects the needs and expectations of the people it is meant to serve.

One prominent international initiative is the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR), which works to promote and advance participatory health research. Its German-speaking network, PartNet, offers a space for exchange among researchers, practitioners and members of the public, while also supporting the development and dissemination of participatory research methods.

In Germany, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) has developed a digitalization strategy aimed at fostering dialogue between science and society. A central focus is on involving citizens more actively in research processes. The BMBF’s research program Innovation Through Collaboration further supports participatory approaches in innovation, funding projects that bring together diverse stakeholders to co-develop solutions to pressing societal challenges (BMBF 2023).

In the research context, patient and public involvement (PPI) plays an increasingly important role. This approach engages patients, caregivers and the wider public throughout the entire research process – from setting priorities and planning studies to conducting research and sharing results.

Participatory health research (PHR) takes this model further by treating affected individuals as equal partners in the research process. The goal is to bridge the gap between science and practice, ensuring that research findings are directly translated into improvements in care and health outcomes.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) follows a similar ethos, emphasizing equal partnership between researchers and community members. This approach is especially valuable for addressing the needs of specific populations – such as marginalized ethnic groups or communities facing health inequities – by co-creating solutions grounded in local knowledge and lived experience.

Citizen science also provides meaningful opportunities for public participation in scientific work. In the health context, this might involve individuals contributing to research by collecting or sharing their own health data, often via smartphone apps or digital tools (NIHR; Wright et al. 2021).

In the field of design, participatory methods offer additional avenues for engagement. Human-centered design (HCD) and user-centered design (UCD) place users at the core of the development process, incorporating their needs, preferences and behaviors into the creation of digital health solutions. These iterative methods engage users throughout the design cycle.

Co-creation and co-design go a step further, inviting users to work side by side with developers as equal partners across all phases of development. This collaborative approach can yield more innovative solutions that reflect the insights and experiences of all stakeholders.

Integrating these research and design approaches can lead to a more robust, inclusive process for developing digital health interventions, systems and services. Even if a national health platform is not a traditional research endeavor, drawing on participatory methods can help ensure it is grounded in the realities of those who use it – and better equipped to serve them.

Overview: Research and design approaches

This approach views research as a collaborative process among scientists, practitioners and individuals directly affected by the issue at hand. The aim is to generate new knowledge and promote both health and equity through shared decision-making, with all participants actively and equally engaged throughout the research process.

CBPR involves communities as equal partners in the research process. It seeks to integrate knowledge and action to drive social change and reduce health disparities – particularly those linked to social, economic or environmental determinants of health.

Citizen science enables members of the public to take an active role in research – for example, by collecting, analyzing or interpreting data. The goal is to expand public engagement in the research enterprise.

These design methodologies place users’ needs, preferences, and behaviors at the forefront of the development process. The objective is to create digital health tools and services that are intuitive, relevant and easy to use.

In co-creation and co-design, users and developers work together as equal partners across all phases of the development process. By incorporating diverse perspectives, these approaches aim to deliver more innovative and responsive solutions.

Recommendations for engaging users in the design of a national health platform

A national health platform grounded in the Trusted Health Ecosystems vision puts patients first. This population is, by nature, highly diverse – and any inclusive approach must also account for the needs of vulnerable groups. That includes addressing barriers related to language, literacy, and digital access to avoid deepening the digital health divide. To ensure the platform reflects users’ needs, expectations and acceptance criteria, a range of engagement formats should be employed – such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, and workshops, conducted both in person and online.

Importantly, the choice of methods should itself be informed by user input, to encourage broad participation and uphold the principle of shared ownership throughout the process. Development should follow an iterative model, with users involved in regular testing and their feedback continuously informing the design.

Patient involvement should be viewed not only as an ethical obligation but as a strategic necessity – essential to building a platform that is truly responsive and widely adopted.

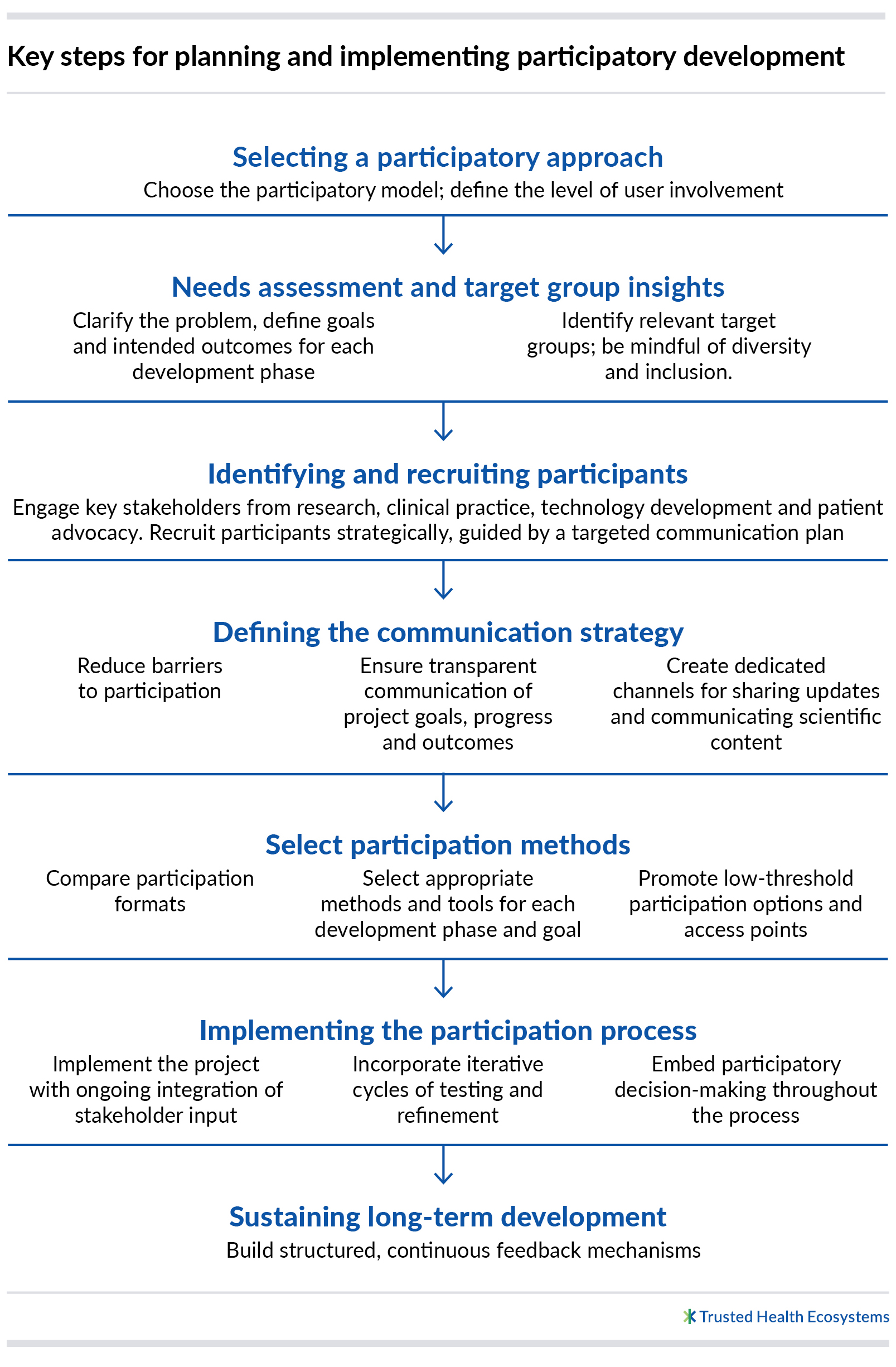

What follows is an outline of key steps for a participatory development process aimed at creating a sustainable and equitable national health platform (OECD 2022).

Challenges and strategic responses

Building a national digital health platform involves a host of challenges that extend well beyond technical implementation. Safeguarding data privacy and security must be paramount to earn and maintain user trust. At the same time, standards for informed consent must be upheld, and ethical considerations thoughtfully addressed. This requires close coordination among developers, legal experts, and ethicists to ensure that digital solutions meet both legal and normative standards.

Interoperability across existing systems and the integration of emerging technologies – such as artificial intelligence and big data – are critical success factors. Digital solutions must align with current infrastructures to be effective and capable of improving care delivery.

For digital tools to be widely adopted, social and digital access barriers must be actively reduced. A range of educational and support initiatives is needed to help the public – including patients – navigate and use new technologies with confidence.

The goal is to prevent the emergence of a digital health divide. Participatory processes can help ensure that the needs of diverse, and particularly vulnerable, groups are reflected in platform development. This includes addressing technical accessibility (e.g., compatibility with screen readers) and language access (e.g., plain language, multilingual interfaces) as part of a broader commitment to inclusivity. Enhancing digital literacy through targeted education and outreach can empower users to actively engage with the evolving digital health ecosystem. Achieving this will require sustained collaboration among educational institutions, healthcare providers and technology developers.

Conclusion

The digital transformation of healthcare is not just a technical challenge – it is a collective societal responsibility. Its long-term success hinges on the meaningful engagement of users. To that end, all stakeholders – policymakers, healthcare providers, developers, digital solution providers, and the research community – must take an active role in involving patients throughout the design processes. Placing the needs and preferences of users at the center of digital health initiatives is essential to building a truly patient-centered system.

Only through sustained collaboration and a shared commitment to prioritizing patients can we ensure that digital healthcare is not only efficient, but also equitable, transparent and inclusive.

Bibliography

BMG – Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2024). Digitalisierung im Gesundheitswesen. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/themen/digitalisierung/digitalisierung-im-gesundheitswesen.html

BMG – Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2023). Digitalisierungsstrategie. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/themen/digitalisierung/digitalisierungsstrategie.html

Fischer, Florian (2020). Digitale Interventionen in Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung: Welche Form der Evidenz haben wir und welche wird benötigt?. Bundesgesundheitsbl 63, 674–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03143-6

Hochmuth, Alexander, Anne-Kathrin Exner & Christoph Dockweiler (2020). Implementierung und partizipative Gestaltung digitaler Gesundheitsinterventionen. Bundesgesundheitsbl 63, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-03079-6

BMBF – Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2023). Partizipationsstrategie Forschung. https://www.bmbf.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/2023/partizipationsstrategie.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

NIHR – National Institute for Health Research (o. D.). What is patient and public involvement and public engagement? School for Primary Care Research. https://www.spcr.nihr.ac.uk/PPI/what-is-patient-and-public-involvement-and-engagement

Wright, Michael, Theresa Allweiss & Nikola Schwersensky (2021). Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung. In: Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA) (Hrsg.). Leitbegriffe der Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention. Glossar zu Konzepten, Strategien und Methoden. https://doi.org/10.17623/BZGA:Q4-i085-2.0

PartNet – Netzwerk für Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung (o. D.). http://partnet-gesundheit.de/ueber-uns/organisatorischer-rahmen/

OECD (2022). OECD Guidelines for Citizen Participation Processes, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f765caf6-en

Authors

Mina Luetkens

The trained physicist has worked for many years in global roles at large pharmaceutical companies, including as a portfolio manager, internal auditor, and controller. Publicly, Mina Luetkens advocates for the position of patients and societal involvement. Her personal focus is on networking the areas of technology and system/culture. With Patients4Digital, she promotes participation in healthcare (participatory research and development) as well as Human Centered Healthcare.

Vera Weirauch

Vera Weirauch is a research assistant in the Healthcare Department at the Fraunhofer Institute for Software and Systems Engineering ISST. Since 2022, she has been bringing her expertise to various research projects on digital and data-driven healthcare of the future. As a doctoral candidate, she is researching participatory procedures in the field of Digital Health and examining the involvement of citizens in the development and evaluation processes of digital health interventions.